|

When the first 65F day of the year falls on a weekend I feel like I've hit the lottery. It means I can suit up and do a full inspection in each of my hives. I'm always a little rusty at the beginning of the year so I like to write down the things I need to look for when I open up each hive. Below you can see the list I made for myself for my first inspection on Sunday. To keep track of everything I see I use this hive inspection form available from my local club: http://www.dcbeekeepers.org/downloadable_files/DCBA_Hive_Inspection_Form.pdf I'm happy to report that all five of my hives made it through the winter and the queens are laying well. Each colony is bringing in lots of pollen and nectar from the early-blooming plants in my neighborhood. Crocus, henbit, corn speedwell, hellebores, witch hazel and the maple trees are all blooming. These early food sources are critical to the survival all kinds of pollinators, not just honeybees. The 2019 beekeeping season looks off to a good start! Checklist: First Hive Inspection of the Year

What I won't be doing today

When I come inside afterwards I'll review my notes and think about what I saw. From this I'll be able to plan what I need to do in the coming week including:

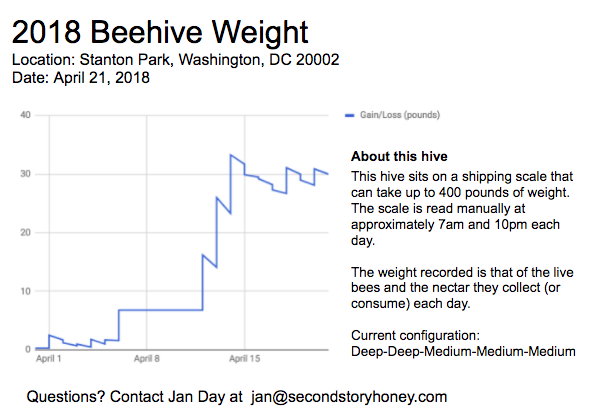

Nectar is 80% water. The bees use this to feed themselves and they will also dry down the nectar to convert it to honey to eat later in the year. Honey is less than 18% water content. The bees fan their wings to evaporate the moisture and dry the nectar down. The sawtooth pattern in the plot of the line is a result of the bees drying off the moisture in the nectar overnight. This pattern will continue as long as the flowers and trees are blooming and continue to give nectar. Last year the nectar flow began at the end of March and continued through mid-June, an unexpectedly long bloom period for Washington, DC. My four hives were so strong and the nectar flow went on for so long that I had to have two harvests - one in June and the second in July. I've only got one hive that is likely to make a honey crop this year so my fingers are crossed we get a nice long bloom!

It took long enough but Spring appears to have finally arrived in DC. Yesterday the weather was a perfect 77F and sunny day which the bees loved. I hope Spring has arrived for you too!

These are the views from the Second Story Apiary on the first and second day of Spring? Can you spot the difference between the two photos? If you spotted the beautiful coating of snow in the second photo you would be right! We got over 4 inches of wet snow on the second day of Spring. Happily, the cold doesn't seem to have hurt the blooms or the bees. The bees were happily flying to and from the hive on the third, much warmer, day of Spring.

To tell the story of life inside a hive I brought a frame filled with honey held safely within a windowed display case so visitors could see what honey looks like when it is still in the honey comb. Few people had ever seen a frame full of honey before and asked lots of questions about it. I also brought a nucleus (aka five-frame) hive so that visitors could see what the inside of a hive looks. It was a great opportunity for visitors to not only see but also smell a beehive. Many people remarked that the inside of a hive smells like honey and beeswax!

Even with the best of intentions sometimes you can’t dampen the instincts of bees to swarm so Repasky shares insights on how to manage the swarm when it happens as well as how to deal with the parent colony in its post-swarm state. Rounding out the book is a chapter on techniques for catching swarms illustrated with photos and tales of swarm catching adventures by the author. Of all the things in this slim volume, my absolute favorite part is Appendix III “Beekeeper Decision Making Chart During Swarm Season.” This flowchart alone is worth the price of the book. I have a laminated photocopy of the flowchart and I make sure to bring it with me on every hive inspection I do from late March to late May. Do yourself and your bees a favor in the next couple of weeks - get a copy of the book and read it from cover to cover so you can anticipate and manage (or mitigate) the 2018 swarm season for your colony. Long live the queen!

Despite the cold, grey, misty weather this morning here in DC I was delighted to see these signs of Spring on my walk with Echo.

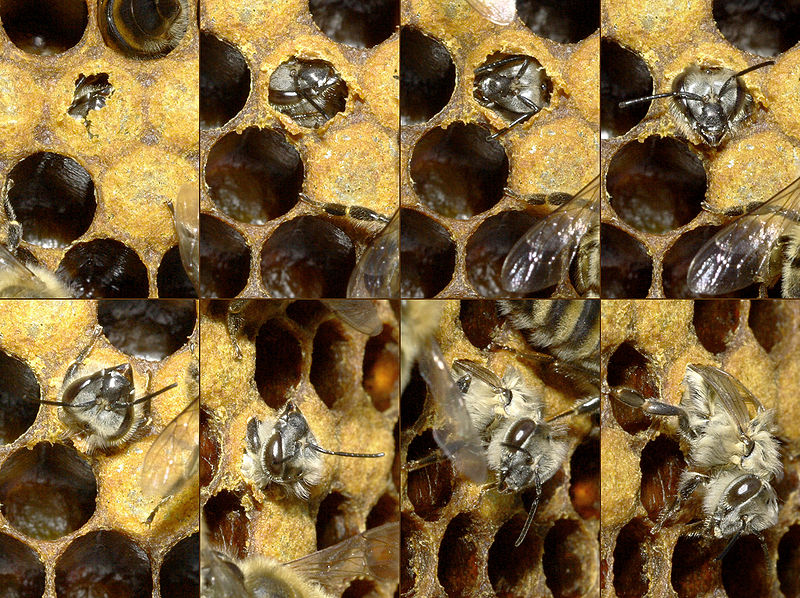

Even though Punxsutawney Phil has declared there are six more weeks of Winter to go, you'd never know it by looking inside one of my beehives. As far as the hive is concerned it is Spring! The queen has been busy for the past few weeks laying eggs. Somehow she has known, despite the long stretches of below-freezing temperatures, that the days are growing longer. This signal has told her it is time to lay eggs, hundreds of them. Now that there are eggs in the brood nest the worker bees must work hard to keep the bee nursery at 96F to ensure the eggs are warm enough. The bees cluster around the eggs and flex their wing muscles to generate heat. This effort takes a lot of energy. They begin to consume their honey stores at a faster rate. This is a dangerous time for the colony. If they consume their Winter honey stores before the Spring bloom begins then they die. But if they don't keep the hive warm enough, the next generation of bees will freeze. As a beekeeper I try to keep a close eye on things and top up their food stores if needed.

Fingers crossed all is well in the hives!

The New York Times had a great article on how to choose a candle stick, holder or platform to display your candles to their finest effect. So many beautiful selections! If you're looking for a candle to use in one of these artistic creations you have come to the right place!

At the time, the abbey beekeepers were learning to work with varieties of newly imported European honeybees and desperate to try to find a strain that could not just survive but flourish in the cold and damp English weather. In this slim volume Brother Adam shares the innovations they made and perfected for their beekeeping equipment, hive management practices and bee breeding. Some of the things he notes as critical to success at Buckfast Abbey:

Insights into Buckfast Abbey hive management practices:

Not everything Brother Adam shares is applicable to beekeeping in our time and place. In the forty years since this book was written researchers have learned a lot about bees, their biology, and of course today there different threats to bee health. In addition, the beekeeping environment Brother Adam is writing about is local to Devon, England not our weather or seasons. Brother Adam writes with a distinct voice thanks to a rich vocabulary and strong opinion on how to manage bees. The book is engaging and accessible to a intermediate-level beekeeper who has familiarity with more specific beekeeping terms and techniques. The photos of Buckfast apiaries and equipment are fascinating to explore. Who would enjoy this book? Anyone who is looking to learn from a legend in beekeeping and who wants to know more about beekeeping techniques, evolution of beekeeping equipment and history of beekeeping. Last but not least, Brother Adam shares his recipes for mead in the last chapter. I fully intend to try the Buckfast recipe after my next honey harvest.

Photo by Kevin Watson Photo by Kevin Watson At the end of each year I like to take time to reflect on what I learned as a beekeeper, think about what I can do next year to be a better beekeeper and set goals for the coming year. What did I learn this year? In my fourth year of beekeeping I learned:

This time of year when the nights are long, the temperatures are cold and we turn the calendar from the old year to the new I get a lot of questions about how my bees are doing. I love questions about bees! Today the bees are safely nestled in their hive grouped in what is known as their winter cluster. The bees primary goal for the winter is to keep their queen alive. The queen is the future of the hive. To protect her, the worker bees pack themselves into a tight ball with their queen at the center. By flexing their flight muscles the 20-30,000 worker bees collectively generate heat - enough to keep their queen a toasty 75F day and night. The bees in the center of this ball constantly shift position and slowly move towards the outside of the cluster to allow the colder bees on the edge of the cluster to take their turn in the toasty core. Along their journey to and from the edge of the cluster to the middle, the bees will eat some of their winter honey stores. On the days that the weather warms above 55F the bees will take turns to make short flights to eliminate their waste. Sometime in late January as the days begin to lengthen, the queen will begin to lay the first eggs of the 2018 season. When she does, the bees in the cluster will increase their efforts to keep the eggs and unhatched larvae at a constant 96F. This work is energy-intensive. To fuel their efforts the colony will consume upwards of 60 to 80 pounds of honey over the course of the winter. This cold and dark time of year is one of mixed emotions for me as a beekeeper because there isn't much I can do for the bees at this point. I'm anxious wondering whether each of my hives has enough honey stores to keep them well fed despite the fact I left more than 80 pounds of honey in each hive. I'm happy for the free time I gain each weekend because I'm not having to actively manage my hives. But most of all I'm hopeful about the new year ahead and the beekeeping adventures I will have.

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed